Depeche Mode Discography Download

Depeche Mode performing in 2006. From left to right: Peter Gordeno, Christian Eigner, Dave Gahan, Martin Gore, and Andy Fletcher | |

| Background information | |

|---|---|

| Origin | Basildon, Essex, England, United Kingdom |

| Genres | |

| Years active | 1980–present |

| Labels | |

| Website | www.depechemode.com |

| Members | |

| Past members | |

The discography of English electronic music group Depeche Mode consists of 14 studio albums, six live albums, ten compilation albums, eight box sets, 13 video albums, 53 singles and 70 music videos. The band's music has been released on several labels, including Some Bizzare, Mute Records, Sire Records, Reprise Records, and Columbia Records.

Depeche Mode – Global Spirit Tour – Live In Stockholm () (flac tracks+.cue plus mp3 320kbps Depeche Mode – Going Backwards (Remixes) – 2017 [iTunes plus AAC m4a] Depeche Mode – Going Backwards (Single) – 2017 [iTunes plus AAC m4a]. ©1998-2018 DEPMOD.COM All Rights Reserved. Depeche Mode - Discography (1981-2017) AAC. Depeche Mode - Discography (1981-2017) AAC is available on a new fast direct download service with over 10,000,000 Files to choose from. Download anything with more then 2000+ Kb/s downloading speed! Come and download depeche mode discography absolutely for free. Fast downloads. Depeche Mode have had forty-eight songs in the UK Singles Chart and #1 albums in UK, US and throughout Europe. According to EMI, Depeche Mode have sold over 100 million albums and singles worldwide, making them the most successful electronic band in music history.

Depeche Mode (/dəˌpɛʃ-, diː-, dɪ-/) are an English electronic band formed in Basildon, Essex, in 1980. The group as of 2019 consists of a trio of Dave Gahan (lead vocals and co-songwriting), Martin Gore (keyboards, guitar, and main songwriting), and Andy Fletcher (keyboards).

Depeche Mode released their debut album Speak & Spell in 1981, bringing the band onto the British new wave scene. Founding member Vince Clarke left after the release of the album; they recorded A Broken Frame as a trio. Gore took over as main songwriter and, later in 1982, Alan Wilder replaced Clarke, establishing a lineup that continued for 13 years.

The band's last albums of the 1980s, Black Celebration and Music for the Masses, established them as a dominant force within the electronic music scene. A highlight of this era was the band's June 1988 concert at the Pasadena Rose Bowl, where they drew a crowd in excess of 60,000 people. In early 1990, they released Violator, an international mainstream success. The following album, Songs of Faith and Devotion in 1993 was also a success, though internal struggles within the band during recording and touring resulted in Wilder's departure in 1995.

Depeche Mode has had 54 songs in the UK Singles Chart and 17 top 10 albums in the UK chart; they have sold more than 100 million records worldwide.[1][2]Q included the band in the list of the '50 Bands That Changed the World!'.[3] Depeche Mode also rank number 98 on VH1's '100 Greatest Artists of All Time'.[4] In December 2016, Billboard named Depeche Mode the 10th most successful dance club artist of all time.[5]

- 1History

- 3Legacy

- 6Discography

- 8References

History[edit]

Formation and debut album (1977–1981)[edit]

Depeche Mode's origins date to 1977, when schoolmates Vince Clarke and Andy Fletcher formed a Cure-influenced[6] band called No Romance In China, with Clarke on vocals and guitar and Fletcher on bass guitar. Fletcher would later recall, 'Why am I in the band? It was accidental right from the beginning. I was actually forced to be in the band. I played the guitar and I had a bass; it was a question of them roping me in.'[7] In 1979, Clarke played guitar in an 'Ultravox rip-off band', The Plan, with friends Robert Marlow and Paul Langwith.[8] In 1978–79, Martin Gore played guitar in an acoustic duo, Norman and the Worms, with school friend Phil Burdett on vocals.[9] In 1979, Marlow, Gore and friend Paul Redmond formed a band called the French Look, with Marlow on vocals/keyboards, Gore on guitar and Redmond on keyboards. In March 1980, Clarke, Gore and Fletcher formed a band called Composition of Sound, with Clarke on vocals/guitar, Gore on keyboards and Fletcher on bass.

Soon after the formation of Composition of Sound, Clarke heard Wirral band Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark (OMD), whose output inspired him to make electronic music.[10][11] Along with OMD, other early influences included the Human League, Daniel Miller and Fad Gadget.[12] Clarke and Fletcher switched to synthesisers, working odd jobs in order to buy the instruments, or borrowing them from friends. Dave Gahan joined the band in 1980 after Clarke heard him perform at a local Scout hutjam session, singing a rendition of David Bowie's 'Heroes',[13] and Depeche Mode were born. Gahan's and Gore's favourite artists included Sparks, Siouxsie and the Banshees,[14]Cabaret Voltaire, Talking Heads and Iggy Pop.[15] Gahan's persona onstage was influenced by Dave Vanian, frontman of The Damned.[16]

When explaining the choice for the new name, taken from French fashion magazine Dépêche mode,[17] Gore said, 'It means hurried fashion or fashion dispatch. I like the sound of that.'[18] However, the magazine's name (and hence the band's) is 'Fashion News' or 'Fashion Update'[19] (dépêche, 'dispatch', from Old Frenchdespesche/despeche or 'news report', and mode or 'fashion').

Gore recalled that the first time the band played as Depeche Mode was a school gig in May 1980.[20] There is a plaque commemorating the gig at the James Hornsby School in Basildon, where Gore and Fletcher were pupils. The band made their recording debut in 1980 on the Some Bizzare Album with the song 'Photographic', later re-recorded for their debut album Speak & Spell.

The band made a demo tape but, instead of mailing the tape to record companies, they would go in and personally deliver it. They would demand the companies play it; according to Dave Gahan, 'most of them would tell us to fuck off. They'd say 'leave the tape with us' and we'd say 'it's our only one'. Then we'd say goodbye and go somewhere else.'[21]

According to Gahan, prior to securing their record contract, they were receiving offers from all the major labels. Phonogram offered them 'money you could never have imagined and all sorts of crazy things like clothes allowances'.[21]

While playing a live gig at the Bridge House in Canning Town,[22] the band were approached by Daniel Miller, an electronic musician and founder of Mute Records, who was interested in their recording a single for his burgeoning label.[23] The result of this verbal contract was their first single, 'Dreaming of Me', recorded in December 1980 and released in February 1981. It reached number 57 in the UK charts. Encouraged by this, the band recorded their second single, 'New Life', which climbed to number 11 in the UK charts and got them an appearance on Top of the Pops. The band went to London by train, carrying their synthesisers all the way to the BBC studios.

The band's next single was 'Just Can't Get Enough'. The synth-pop single became the band's first UK top ten hit. The video is the only one of the band's videos to feature Vince Clarke. Depeche Mode's debut album, Speak & Spell, was released in October 1981 and peaked at number ten on the UK album charts.[24] Critical reviews were mixed; Melody Maker described it as a 'great album … one they had to make to conquer fresh audiences and please the fans who just can't get enough',[25] while Rolling Stone was more critical, calling the album 'PG-rated fluff'.[26]

Clarke departs and Wilder joins (1981–1982)[edit]

Clarke began to voice his discomfort at the direction the band was taking, saying 'there was never enough time to do anything. Not with all the interviews and photo sessions'.[27] Clarke also said he was sick of touring, which Gahan said years later was 'bullshit to be quite honest.'[21] Gahan went on to say he 'suddenly lost interest in it and he started getting letters from fans asking what kind of socks he wore.'[21] In November 1981, Clarke publicly announced that he was leaving Depeche Mode.[28]

Soon afterwards, Clarke joined up with blues singer Alison Moyet to form Yazoo (or Yaz in the United States). Initial talk of Clarke's continuing to write material for Depeche Mode ultimately amounted to nothing. According to third-party sources, Clarke offered the remaining members of Depeche Mode the track 'Only You', but they declined.[29] Clarke, however, denied in an interview that such an offer ever took place saying, 'I don't know where that came from. That's not true.'[30] The song went on to become a UK Top 3 hit for Yazoo. Gore, who had written 'Tora! Tora! Tora!' and the instrumental 'Big Muff' for Speak & Spell, became the band's main lyricist.[31]

In late 1981, the band placed an anonymous ad in Melody Maker looking for another musician: 'Name band, synthesise, must be under twenty-one.'[13]Alan Wilder, a classically trained keyboardist from West London, responded and, after two auditions and despite being 22 years old, was hired in early 1982, initially on a trial basis as a touring member.[32] Wilder would later be called the 'Musical Director' of the band, responsible for the band's sound until his departure in 1995.[7] As producer Flood would say, '[Alan] is sort of the craftsman, Martin's the idea man and [Dave] is the attitude.'[7]

In January 1982, the band released 'See You', their first single without Clarke, which managed to beat all three Clarke-penned singles in the UK charts, reaching number six.[33] The following tour saw the band playing their first shows in North America. Two more singles, 'The Meaning of Love' and 'Leave in Silence', were released ahead of the band's second studio album, on which they began work in July 1982. Daniel Miller informed Wilder that he was not needed for the recording of the album, as the core trio wanted to prove they could succeed without Vince Clarke.[34]A Broken Frame was released that September, and the following month the band began their 1982 tour. A non-album single, 'Get the Balance Right!', was released in January 1983, the first Depeche Mode track to be recorded with Wilder.[35]

Construction Time Again (1983)[edit]

For their third album, Construction Time Again, Depeche Mode worked with producer Gareth Jones, at John Foxx's Garden Studios and at Hansa Studios in West Berlin (where much of David Bowie's trilogy of seminal electronic albums featuring Brian Eno had been produced). The album saw a dramatic shift in the group's sound, due in part to Wilder's introduction of the Synclavier and E-mu Emulatorsamplers.[36] By sampling the noises of everyday objects, the band created an eclectic, industrial-influenced sound, with similarities to groups such as the Art of Noise and Einstürzende Neubauten (the latter becoming Mute labelmates in 1983).[37]

'Everything Counts' rose to number six in the UK, also reaching the top 30 in Ireland, South Africa, Switzerland, Sweden and West Germany.[24] Wilder contributed two songs to the album, 'The Landscape Is Changing' and 'Two Minute Warning'. In September 1983, to promote Construction Time Again, the band launched a European concert tour.

Some Great Reward and growing international success (1984–1985)[edit]

In their early years, Depeche Mode had only really attained success in Europe and Australia.[citation needed] This changed in March 1984, when they released the single 'People Are People'. The song became a hit, reaching No. 2 in Ireland and Poland, No. 4 in the UK and Switzerland, and No. 1 in West Germany — the first time a DM single topped a country's singles chart — where it was used as the theme to West German TV's coverage of the 1984 Olympics.[38] Beyond this European success, the song also reached No. 13 on the US charts in mid-1985, the first appearance of a DM single on the Billboard Hot 100, and was a Top 20 hit in Canada. 'People Are People' became an anthem for the LGBT community,[39] regularly played at gay establishments and gay pride festivals in the late 1980s. Sire, the band's North American record label, released a compilation of the same name which included tracks from A Broken Frame and Construction Time Again as well as several B-sides.

On the American tour, the band was, according to Gore, 'shocked by the way the fans were turning up in droves at the concerts'.[21] He said that although the concerts were selling well, Depeche Mode struggled to sell records.[21]

In September 1984, Some Great Reward was released. Melody Maker claimed that the album made one 'sit up and take notice of what is happening here, right under your nose.'[40] In contrast to the political and environmental subjects addressed on the previous album, the songs on Some Great Reward were mostly concerned with more personal themes such as sexual politics ('Master and Servant'), adulterous relationships ('Lie to Me'), and arbitrary divine justice ('Blasphemous Rumours'). Also included was the first Martin Gore ballad, 'Somebody' — such songs would become a feature of all following albums.[citation needed] 'Somebody' was released as a double A-side with 'Blasphemous Rumours', and was the first single with Gore on lead vocal. Some Great Reward became the first Depeche Mode album to enter the US album charts, and made the Top 10 in several European countries.[citation needed]

The World We Live In and Live in Hamburg was the band's first video release, almost an entire concert from their 1984 Some Great Reward Tour. In July 1985, the band played their first-ever concerts behind the Iron Curtain, in Budapest and Warsaw.[41] In October 1985, Mute released a compilation, The Singles 81→85 (Catching Up with Depeche Mode in the US), which included the two non-album hit singles 'Shake the Disease' and 'It's Called a Heart' along with their B-sides.

In the United States, the band's music had first gained prominence on college radio and modern rock stations such as KROQ in Los Angeles, KQAK ('The Quake') in San Francisco, WFNX in Boston and WLIR on Long Island, New York, and hence they appealed primarily to an alternative audience who were disenfranchised with the predominance of 'soft rock and 'disco hell'[42] on the radio. This view of the band was in sharp contrast to how the band was perceived in Europe, despite the increasingly dark and serious tone in their songs.[43] In Germany, France, and other European countries, Depeche Mode were considered teen idols and regularly featured in European teen magazines, becoming one of the most famous synth-pop bands in the mid-'80s.

Black Celebration (1986)[edit]

Depeche Mode's musical style shifted slightly again in 1986 with the release of their fifteenth single, 'Stripped', and its accompanying album Black Celebration. Retaining their often imaginative sampling and beginning to move away from the 'industrial pop' sound that had characterised their previous two LPs, the band introduced an ominous, highly atmospheric and textured sound. Gore's lyrics also took on a darker tone and became even more pessimistic.

The music video for 'A Question of Time' was the first to be directed by Anton Corbijn, beginning a working relationship that continues to the present day. Corbijn has directed a further 20 of the band's videos (the latest being 2017's 'Where's the Revolution.') He has also filmed some of their live performances, and designed stage sets, as well as most covers for albums and singles from Violator and onwards.

Music for the Masses and 101 (1987–1988)[edit]

1987's Music for the Masses saw further alterations in the band's sound and working methods. For the first time a producer not related to Mute Records, Dave Bascombe, was called to assist with the recording sessions, although, according to Alan Wilder, Bascombe's role ended up being more that of engineer.[44] In making the album, the band largely eschewed sampling in favour of synthesizer experimentation.[45] While chart performance of the singles 'Strangelove', 'Never Let Me Down Again' and 'Behind the Wheel' proved to be disappointing in the UK, they performed well in countries such as Canada, Brazil, West Germany, South Africa, Sweden and Switzerland, often reaching the top 10. Record Mirror described Music for the Masses as 'the most accomplished and sexy Mode album to date'.[46] The album also made a breakthrough in the American market.[citation needed]

The Music for the Masses Tour began 22 October 1987. On 7 March 1988, with no previous announcement that they would be the headlining act, Depeche Mode played in the Werner-Seelenbinder-Halle, East Berlin,[47] becoming one of the few Western groups to perform in the Communist East Germany. They also performed concerts in Budapest and Prague in 1988,[48] both at the time also Communist.

The world tour ended 18 June 1988 with a concert at the PasadenaRose Bowl with paid attendance of 60,453,[49] the highest in eight years for the venue.[citation needed] The tour was a breakthrough for the band[citation needed] and a massive success[citation needed] in the United States. It was documented in 101 – a concert film by D. A. Pennebaker and its accompanying soundtrack album. The film is notable for its portrayal of fan interaction.[50][51] Alan Wilder is credited with coming up with the title, noting that the performance was the 101st and final performance of the tour.[52] On 7 September 1988, Depeche Mode performed 'Strangelove' at the 1988 MTV Video Music Awards at the Universal Amphitheatre in Los Angeles.[53]

Violator and worldwide fame (1989–1991)[edit]

In mid-1989, the band began recording in Milan with producer Flood and engineer François Kevorkian. The initial result of this session was the single 'Personal Jesus.' Prior to its release, a marketing campaign was launched with advertisements placed in the personals columns of UK regional newspapers with the words 'Your own personal Jesus.' Later, the ads included a phone number one could dial to hear the song. The resulting furor helped propel the single to number 13 on the UK charts, becoming one of their biggest sellers to date; in the United States, it was their first gold single and their first Top 40 hit since 'People Are People', eventually becoming the biggest-selling 12-inch single in Warner Records' history up to that point.[54]

Martin Gore, stated to NME – July 1990.[55]

Released in January 1990, 'Enjoy the Silence' reached number six in the UK (the first Top 10 hit in that country since 'Master And Servant'). A few months later in the US, it reached number eight and earned the band a second gold single. It won 'Best British single' at the 1991 Brit Awards.[56] To promote their new album, Violator, the band held an in-store autograph signing at Wherehouse Entertainment in Los Angeles. The event attracted approximately 20,000 fans and turned into a near riot. Some who attended were injured by being pressed against the store's glass by the crowd.[57] As an apology to the fans who were injured, the band released a limited edition cassette tape to fans living in Los Angeles, distributed through radio station KROQ (the sponsor of the Wherehouse event).

Violator was the first Depeche Mode album to enter the Top 10 of the Billboard 200, reaching Number 7 and staying 74 weeks in the chart. It was certified triple platinum in America,[58] selling over 4.5 million units there. It remains the band's best selling album worldwide.[citation needed] Two more singles from the album — 'Policy of Truth' and 'World in My Eyes' — were hits in the UK, with the former also charting in the US.

Flood, on Giants Stadium concert.[59]

The World Violation Tour saw the band play several stadium shows in the US. 42,000 tickets were sold within four hours for a show at Giants Stadium, and 48,000 tickets were sold within half-an-hour of going on sale for a show at Dodger Stadium.[60] An estimated 1.2 million fans saw this tour worldwide.[7]

In 1991, Depeche Mode contribution 'Death's Door' was released on the soundtrack album for the film Until the End of the World. Film director Wim Wenders had challenged musical artists to write music the way they imagined they would in the year 2000, the setting of the movie.

Songs of Faith and Devotion and Wilder's departure (1992–1995)[edit]

The members of Depeche Mode regrouped in Madrid in January 1992, Dave Gahan had become interested in the new grunge scene sweeping the U.S. and was influenced by the likes of Jane's Addiction, Soundgarden and Nirvana.[61]

Alan Wilder on the genesis of some of the sounds on Songs of Faith and Devotion, stated to Pulse! magazine – May 1993.[7]

In 1993, Songs of Faith and Devotion, again with Flood producing, saw them experimenting with arrangements based as much on heavily distorted electric guitars and live drums (played by Alan Wilder, whose debut as a studio drummer had come on the Violator track 'Clean') as on synthesizers.[62] Live strings, uilleann pipes and female gospel vocals were other new additions to the band's sound. The album debuted at number one in both the UK and the US, only the sixth British act to achieve such a distinction to date.[59] The first single from the album was the grunge-influenced 'I Feel You.' The gospel influences are most noticeable on the album's third single, 'Condemnation.' Interviews given by the band during this period tended to be conducted separately, unlike earlier albums, where the band was interviewed as a group.[7]

Depeche Mode Songs

The Devotional world tour followed, documented by a concert film of the same name. The film was directed by Anton Corbijn, and in 1995 earned the band their first Grammy nomination.[63] The band's second live album, Songs of Faith and Devotion Live, was released in December 1993. The tour continued into 1994 with the Exotic Tour, which began in February 1994 in South Africa, and ended in April in Mexico. The final leg of the tour, consisting of more North American dates, followed shortly thereafter and ran until July. As a whole, the Devotional Tour is to date the longest and most geographically diverse Depeche Mode tour, spanning fourteen months and 159 individual performances.

Q magazine described the 1993 Devotional Tour as 'The Most Debauched Rock'n'Roll Tour Ever.'[64] According to The Independent, the 'smack-blasted' Gahan 'required cortisone shots just to perform, borderline alcoholic Gore suffered two stress-induced seizures, and Andrew Fletcher's deepening depression resulted, in the summer of 1994, in a full nervous breakdown.'[65] Fletcher declined to participate in the second half of the Exotic Tour due to mental instability;[citation needed] he was replaced on stage by Daryl Bamonte, who had worked with the band as a personal assistant since the beginning of their career in 1980.[66][67]

In June 1995, Alan Wilder announced that he was leaving Depeche Mode, explaining:

Since joining in 1982, I have continually striven to give total energy, enthusiasm and commitment to the furthering of the group's success, and in spite of a consistent imbalance in the distribution of the workload, willingly offered this. Unfortunately, within the group, this level of input never received the respect and acknowledgement that it warrants.[68]

He continued to work on his personal project Recoil, releasing a fourth album (Unsound Methods) in 1997.

Ultra (1996–2000)[edit]

30 second sample from Depeche Mode's 'Barrel of a Gun'. | |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Despite Gahan's increasingly severe personal problems, Gore tried repeatedly during 1995 and 1996 to get the band recording again. However, Gahan would rarely turn up to scheduled sessions, and when he did, it would take weeks to get any vocals recorded; one six-week session at Electric Lady in New York produced just one usable vocal (for 'Sister of Night'), and even that was pieced together from multiple takes.[69] Gore was forced to contemplate breaking the band up and considered releasing the songs he had written as a solo album.[70] In mid-1996, after his near-fatal overdose, Gahan entered a court-ordered drug rehabilitation program to battle his addiction to cocaine and heroin.[71] With Gahan out of rehab in 1996, Depeche Mode held recording sessions with producer Tim Simenon.

Preceded by two singles, 'Barrel of a Gun' and 'It's No Good', the album Ultra was released in April 1997. The album debuted at No. 1 in the UK (as well as Germany), and No. 5 in the US. The band did not tour in support of the album, with Fletcher quoted as saying: 'We're not fit enough. Dave's only eight months into his sobriety, and our bodies are telling us to spend time with our families.'[72] As part of the promotion for the release of the album, they did perform two short concerts in London and Los Angeles, called 'Ultra Parties.'[73]Ultra spawned two further singles, 'Home' and 'Useless'.

A second singles compilation, The Singles 86–98, was released in 1998, preceded by the new single 'Only When I Lose Myself', which had been recorded during the Ultra sessions. In April 1998, Depeche Mode held a press conference at the Hyatt Hotel in Cologne to announce The Singles Tour.[74] The tour was the first to feature two backing musicians in place of Alan Wilder—Austrian drummer Christian Eigner and British keyboardist Peter Gordeno.

Exciter (2001–2004)[edit]

In 2001, Depeche Mode released Exciter, produced by Mark Bell (of techno group LFO). Bell introduced a minimalist, digital sound to much of the album, influenced by IDM and glitch. 'Dream On', 'I Feel Loved', 'Freelove' and 'Goodnight Lovers' were released as singles in 2001 and 2002. Critical response to the album was mixed, with reasonably positive reviews from some magazines (NME, Rolling Stone and LA Weekly), while others (including Q magazine, PopMatters, and Pitchfork) derided it as sounding underproduced, dull and lacklustre.[75]

In March 2001, Depeche Mode held a press conference at the Valentino Hotel in Hamburg to announce the Exciter Tour.[76] The tour featured 84 performances for over 1.5 million fans in 24 countries.[77] The concerts held in Paris at the Palais Omnisports de Paris-Bercy were filmed and later released in May 2002 as a live DVD entitled One Night in Paris.

In October 2002 the band won the first-ever Q magazine 'Innovation Award'.[78]

In 2003, Gahan released his first solo album, Paper Monsters, and toured to promote the record. Also released in 2003 was Gore's second solo album Counterfeit².[79] Fletcher founded his own record label, Toast Hawaii, specialising in promoting electronic music.

A new remix compilation album, Remixes 81–04, was released in 2004, featuring new and unreleased promo mixes of the band's singles from 1981 to 2004. A new version of 'Enjoy the Silence', remixed by Mike Shinoda of Linkin Park, 'Enjoy the Silence 04', was released as a single and reached No. 7 on the UK charts.

Playing the Angel (2005–2007)[edit]

In October 2005, the band released their 11th studio album Playing the Angel. Produced by Ben Hillier, the album peaked at No. 1 in 18 countries and featured the hit single 'Precious'. This is the first Depeche Mode album to feature lyrics written by Gahan and, consequently, the first album since 1984's Some Great Reward featuring songs not written by Gore. 'Suffer Well' was the first ever post-Clarke Depeche Mode single not to be written by Gore (lyrics by Gahan, music by Philpott/Eigner). The final single from the album was 'John the Revelator', an uptempo[citation needed] electronic track with a running religious theme, accompanied by 'Lilian', a lush track[citation needed] that was a hit in many clubs all over the world.[citation needed]

To promote Playing the Angel, the band launched Touring the Angel, a concert tour of Europe and North America that began in November 2005 and ran for nine months. During the last two legs of the tour Depeche Mode headlined a number of festivals including the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival and the O2 Wireless Festival. In total, the band played to more than 2.8 million people across 31 countries and the tour was one of the highest grossing and critically acclaimed tours of 2005/06.[2] Speaking about the tour, Gahan praised it as 'probably the most enjoyable, rewarding live shows we've ever done. The new material was just waiting to be played live. It took on a life of its own. With the energy of the crowds, it just came to life.'[80] Two shows at Milan's Fila Forum were filmed and edited into a concert film, released on DVD as Touring the Angel: Live in Milan.[81]

23 second sample from Depeche Mode's 'Precious'. | |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

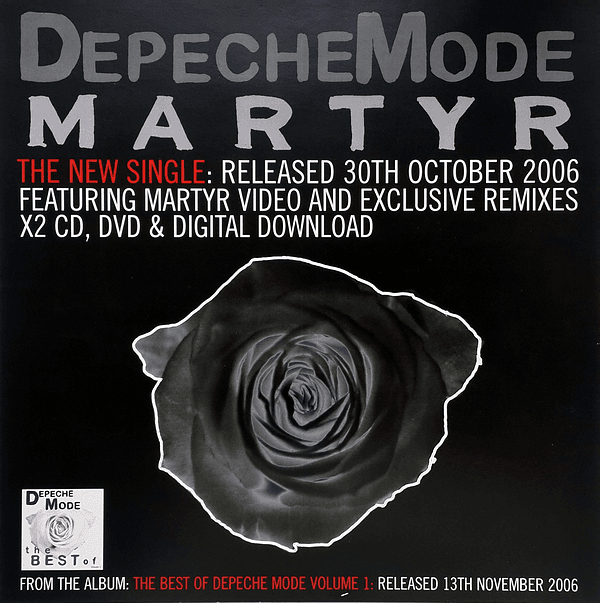

A 'best-of' compilation was released in November 2006, entitled The Best Of, Volume 1 featuring a new single 'Martyr', an outtake from the Playing the Angel sessions. Later that month Depeche Mode received the MTV Europe Music Award in the Best Group category.[82]

Carlisle PennDOT Photo License Center. 950 Walnut Bottom Road Stonehedge Square Carlisle, PA 17013 (717) 412-5300. Local Drivers Ed and Schools - Driving School and Drivers Ed. DMV Locations Carlisle Pennsylvania Report a Bug. Carlisle drivers license center hours. Carlisle PennDOT Driver License Center hours of operation, address, available services & more.

In December 2006, iTunes released The Complete Depeche Mode as its fourth ever digital box-set.[83]

In August 2007, during promotion for Dave Gahan's second solo album, Hourglass, it was announced that Depeche Mode were heading back in studio in early 2008 to work on a new album.[84]

Sounds of the Universe (2008–2011)[edit]

In May 2008, the band returned to the studio with producer Ben Hillier to work on some songs that Martin Gore had demoed at his home studio in Santa Barbara, California. Later that year it was announced that Depeche Mode were splitting from their long-term US label, Warner Music, and signing with EMI Music worldwide.[85] The album was created in four sessions, two in New York and two in Santa Barbara. A total of 22 songs were recorded, with the standard album being 13 songs in length while many of the others were released in subsequent deluxe editions.[86]

On 15 January 2009, the official Depeche Mode website announced that the band's 12th studio album would be called Sounds of the Universe.[87] The album was released in April 2009, also made available through an iTunes Pass, where the buyer received individual tracks in the weeks leading up to official release date. Andy Fletcher says the idea for their iTunes Pass was a combination of the band's and iTunes': 'I think the digital and record companies are starting to get their act together. They were very lazy in the first 10 years when downloads came in. Now they're collaborating more and coming up with interesting ideas for fans to buy products.'[88] The album went to number one in 21 countries. Critical response was generally positive and it was nominated for a Grammy in the Best Alternative Album category.[89] 'Wrong' was the first single from the album, released digitally in February 2009. Subsequent singles were 'Peace' and the double A-side 'Fragile Tension / Hole to Feed'. In addition, 'Perfect' was released as a promotional-only (non-commercial) single in the United States.

U2 Discography

On 23 April 2009, Depeche Mode performed for the television program Jimmy Kimmel Live! at the famed corner of Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street, drawing more than 12,000 fans, which was the largest audience the program had seen since its 2003 premiere, with a performance by Coldplay.[90]

In May 2009, the band embarked on a concert tour in support of the album — called Tour of the Universe; it had been announced at a press conference in October 2008 at the Olympiastadion in Berlin.[91] There was a warm up show in Luxembourg and it officially started on 10 May 2009 in Tel Aviv. The first leg of the tour was disrupted when Dave Gahan was struck down with gastroenteritis. During treatment, doctors found and removed a low grade tumour from the singer's bladder. Gahan's illness caused 16 concerts to be cancelled, but several of the shows were rescheduled for 2010.[92] The band headlined the Lollapalooza festival during the North American leg of the tour. The tour also took the band back to South America for the first time since 1994's Exotic Tour. During the final European leg, the band played a show at London's Royal Albert Hall in aid of the Teenage Cancer Trust, where former member Alan Wilder joined Martin Gore on stage for a performance of 'Somebody'.[93][94] In total the band played to more than 2.7 million people across 32 countries and the tour was one of the most profitable in America in 2009.[95][96] The concerts held at Palau Sant Jordi, Barcelona, Spain were filmed and later released on DVD and Blu-ray Disc release entitled Tour of the Universe: Barcelona 20/21.11.09.[97] In March 2010, Depeche Mode won the award for 'Best International Group – Rock / Pop' at the ECHO Awards in Germany.[98]

On 6 June 2011, as the final commitment to their contract with EMI,[99] the band released a remixcompilation album, entitled Remixes 2: 81–11 that features remixes by former members Vince Clarke and Alan Wilder.[100][101] Other remixers involved with the project were Nick Rhodes of Duran Duran,[102]Röyksopp, Karlsson & Winnberg of Miike Snow, Eric Prydz, Clark and more.[103] A new remix of 'Personal Jesus' by Stargate, entitled 'Personal Jesus 2011', was released as a single on 30 May 2011, in support of the compilation.

Depeche Mode contributed their cover of the U2 song 'So Cruel' to the tribute album AHK-toong BAY-bi Covered honouring the 20th anniversary of Achtung Baby, a 1991 album by U2. The compilation CD was released with the December 2011 issue of Q.[104][105]

Delta Machine (2012–2015)[edit]

In October 2012 during a press conference in Paris, Dave Gahan, Martin Gore and Andy Fletcher announced plans for a new album and a 2013 worldwide tour starting from Tel Aviv and continuing in Europe and North America.[106] Martin Gore revealed that Flood mixed the album, marking the producer's first studio collaboration with the band since 1993's Songs of Faith and Devotion.

In December 2012, the band officially announced signing a worldwide deal with Columbia Records and releasing a new album in March 2013.[107] On 24 January 2013, it was confirmed that the album was titled Delta Machine.[108] 'Heaven', the debut single from Delta Machine was released commercially on Friday 1 February 2013 (although not in the UK). The release date in the UK was pushed back to 18 March 2013 (17 March 2013 on iTunes). The physical release still bore the Mute Records logo, even though the band have now severed ties with their long standing label. Andy Fletcher mentioned in an interview this was due to their 'devotion' to the label and with the band's insistence.

In March, the band announced North American dates to its Delta Machine summer tour, starting 22 August from Detroit and ending 8 October in Phoenix.[109] In June, other European dates[110] were confirmed for early 2014. The final gig of Delta Machine Tour took place in Moscow (Russia) on 7 March 2014, at Olimpiski venue.

That month, Depeche Mode won the award for 'Best International Group – Rock / Pop' at the ECHO Awards in Germany. Also they were nominated at the category 'Album des Jahres (national oder international)' for Delta Machine, but lost against Helene Fischer's Farbenspiel.[111][112]

On 8 October 2014, the band announced Live in Berlin, the new video and audio release filmed and recorded at the O2 World in Berlin, Germany in November 2013 during the Delta Machine Tour. It was released on 17 November 2014 worldwide.[113]

In a 2015 Rolling Stone interview celebrating the 25th anniversary of Violator, Martin Gore stated that Johnny Cash's cover of 'Personal Jesus' is his favorite cover version of a Depeche Mode song.[114]

Spirit (2016–present)[edit]

On 25 January 2016, Martin Gore announced a projected return to the recording studio in April, with both Gore and Gahan having already written and demoed new songs.[115]

In September, the official Depeche Mode Facebook page hinted at a new release, later confirmed by the band to be a music video compilation, Video Singles Collection, scheduled for release in November by Sony.[116][117] In October 2016, the band announced that their fourteenth album, titled Spirit and produced by James Ford, would be released in spring 2017.[118] The group has also been nominated for the 2018 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[119]

'Where's the Revolution', the lead single from Spirit, was released 3 February 2017, along with its lyric video. The official video was published a week later, on 9 February.[120] The Global Spirit Tour officially kicked off on 5 May 2017 with a performance in Stockholm, Sweden, at the Friends Arena. The first leg of the tour covered European countries only, ending with a final stadium show in Cluj-Napoca, Romania, at the Cluj Arena. The second leg of the tour covered North America and returned to Europe. The North America leg of the tour kicked off in Salt Lake City, Utah, on 23 August, at the USANA Amphitheatre. The band remained in North America until 15 November when they left for Dublin to resume the European leg. The band ended the tour in Europe with a final show on 25 July 2018 in Berlin, Germany, at the Waldbühne.[121][122]

Artistry[edit]

Depeche Mode drew its artistic influences from a wide range of artists and scenes, such as Kraftwerk,[123]David Bowie, The Clash,[124]Roxy Music and Brian Eno,[125]Elvis Presley, the Velvet Underground,[126] and blues.[127] Depeche Mode's music has mainly been described as synth-pop,[20][94][128][129][130][131]new wave,[100][128][132][133]electronic rock,[134][135][136][137]dance-rock[138][139]alternative rock,[131]arena rock[140] and pop rock.[141] The band also experimented with various other genres throughout its career, including avant-garde, electronica, pop, soul, techno, industrial rock and heavy metal.[142]

Depeche Mode were considered a teen pop band during their early period in the UK, and interviewed in teen pop magazines such as Smash Hits.[143][144] Following the departure of Vince Clarke, their music began to take on a darker tone, establishing a darker sound in the band's music, as Martin Gore assumed lead songwriting duties.[131] Gore's lyrics included themes such as sex, religion, and politics.[145] Gore has stated he feels lyrical themes which tackle issues related to solitude and loneliness are a better representation of reality, whereas he finds 'happy songs' fake and unrealistic.[146] At the same time, he asserts that the band's music contains 'an element of hope.'[147]

Legacy[edit]

Depeche Mode have released a total of 14 studio albums, 10 compilation albums, six live albums, eight box sets, 13 video albums, 71 music videos, and 54 singles. They have sold over 100 million records and played live to more than 30 million fans worldwide. The band have had 50 songs in the UK Singles Chart, and one US and two UK number-one albums.[148] In addition, all of their studio albums have reached the UK Top 10 and their albums have spent over 210 weeks on the UK Charts.[24]

Depeche Mode Discogs

Music critic Sasha Frere-Jones claimed that 'the last serious English influence was Depeche Mode, who seem more and more significant as time passes.'[149] Depeche Mode's releases have been nominated for five Grammy Awards: Devotional for Best Long Form Music Video; 'I Feel Loved' and 'Suffer Well', both for Best Dance Recording; Sounds of the Universe for Best Alternative Album; and 'Wrong' for Best Short Form Music Video. In addition, Depeche Mode have been honoured with a Brit Award for 'Enjoy the Silence' in the Best British Single category, the first-ever Q Magazine Innovation Award, and an Ivor Novello Award for Martin Gore in the category of International Achievement.

Depeche Mode were called 'the most popular electronic band the world has ever known' by Q magazine,[150] 'one of the greatest British pop groups of all time' by The Sunday Telegraph,[151] and 'the quintessential eighties techno-pop band' by Rolling Stone[129] and AllMusic.[128] They were ranked No. 2 on Electronic Music Realm's list of The 100 Greatest Artists of Electronic Music,[152] ranked No. 158 on Acclaimed Music's list of Top 1000 Artists of All Time[153] and Q Magazine included them on their list of '50 bands that changed the world'.[3] In an interview in 2009, Simple Minds lead singer Jim Kerr argued that Depeche Mode and U2 were the only contemporaries of his band which could be said to have 'stayed constantly relevant'.[154]

Influence[edit]

Several major artists have cited the band as an influence, including: No Doubt,[155]The Killers,[156][157]Crosses,[156]Coldplay,[156]Lady Gaga,[156]Muse,[156]Linkin Park,[158][159]The Crystal Method,[160]Fear Factory,[161]La Roux,[162]Gotye,[163]Rammstein,[164][165]a-ha,[166]Arcade Fire,[167]Nine Inch Nails,[131] and Chvrches.[168]

Depeche Mode contemporaries Pet Shop Boys[169][170] and Gary Numan[171] have also cited the band as an influence.

The dark themes and moods of Depeche Mode's lyrics and music have been enjoyed by several heavy metal artists, and the band influenced acts such as Marilyn Manson, and Deftones.[164] They have also been named as an influence on Detroit techno[131] and indie rock.[172]

Charity work[edit]

Early in their career, Depeche Mode were dismissive of benefit concerts such as Live Aid. Martin himself stated, 'If these bands really care so much, they should just donate the money and let that be it. Why can't they do it without all the surrounding hype?'.[41] But in recent years, the band have applied their celebrity and cultural longevity to help promote and raise funds for several notable charity endeavours. They lent their support to high-profile charities such as MusiCares, Cancer Research UK and the Teenage Cancer Trust. The band has also supported the Small Steps Project, a humanitarian organisation based in the United Kingdom, aiming to assist economically disadvantaged children into education.[173] Since 2010, Depeche Mode have partnered with Swiss watchmaker Hublot to support Charity: Water, aimed at the provision of clean drinking water in developing countries.[174] In 2014, the partnership hosted a gala and fundraiser at the TsUM building in Moscow, raising $1.4 million for the charity.[175]

So, respect to the original uploaders! Rocksmith 2014 crack for custom plug. To run the game, you simply need to copy the files from the folders of updates and DLCs to the game's folder and overwrite. I've collected the rest from around the internet. Here's the order: 1 Update 1 2 Update 2 3 Imports from the original Rocksmith 4 DLCs for the new Rocksmith 5 Crack This is the order I used, and the game works perfectly for me.

Band members[edit]

Current members

- Andy Fletcher– keyboards, backing vocals, bass guitar (1980–present)

- Martin Gore– keyboards, backing and lead vocals, guitars (1980–present)

- Dave Gahan– lead vocals (1980–present)

Touring members

- Christian Eigner– drums, percussion (1997–present)

- Peter Gordeno– keyboards, bass guitar, piano, backing vocals (1998–present)

Former members

- Vince Clarke– keyboards, lead and backing vocals, guitars (1980–1981)

- Alan Wilder– keyboards, piano, drums, backing vocals (1982–1995; one-off show in 2010)

- Timeline

Discography[edit]

Studio albums[edit]

- Speak & Spell (1981)

- A Broken Frame (1982)

- Construction Time Again (1983)

- Some Great Reward (1984)

- Black Celebration (1986)

- Music for the Masses (1987)

- Violator (1990)

- Songs of Faith and Devotion (1993)

- Ultra (1997)

- Exciter (2001)

- Playing the Angel (2005)

- Sounds of the Universe (2009)

- Delta Machine (2013)

- Spirit (2017)

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^'Depeche Mode mit Weltpremiere beim ECHO' (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie. 3 February 2009. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2014.Cite uses deprecated parameter

deadurl=(help) - ^ abMason, Kerri (23 March 2009). 'Depeche Mode Prepares For Tour Of The Universe'. Billboard. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ ab'Q – 50 Bands That Changed The World!'. Q. No. 214. Rocklist.net. May 2004. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ^brandon (13 April 2011). 'VH1 100 Greatest Artists Of All Time'. Stereogum. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ^'Greatest of All Time Top Dance Club Artists : Page 1'. Billboard. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^Miller 2004, p. 14.

- ^ abcdefWeidenbaum, Marc (May 1993). 'Fashion Victims'. Pulse! magazine. No. 114. pp. 48–53.

- ^'Interviews – 'Robert Marlow Interview (1999)''. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012.Cite uses deprecated parameter

deadurl=(help). Erasureinfo.com. - ^'Phil Burdett – Biography'. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011..

- ^'Erasure'. The O-Zone. 29 November 1995. 8 minutes in. BBC Two. British Broadcasting Corporation.

When I was 18 or 19 I heard a single called 'Electricity' by Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark. It sounded so different from anything I'd heard; that really made me want to make electronic music, 'cause it was so unique.

- ^Miller 2004, p. 41: What motivated me to actually buy a synthesiser was, again, probably Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark's 'Almost'.. not that I don't like Gary Numan; don't get me wrong, I was blown away by him on Top of the Pops – but OMD sounded more home-made, and I suddenly thought, 'I can do that!' There was this sudden connection.

- ^'Synth Britannia (Part Two: Construction Time Again)'. Britannia. 16 October 2009. 4 minutes in. BBC Four. British Broadcasting Corporation.

When I first started playing synthesizers it [my inspiration] would have been people like the Human League; Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark, their very first album; I was a big fan of Daniel Miller's work, as the Silicon Teens and as the Normal; and also of Fad Gadget, who was on Mute Records.

- ^ abShaw, William (April 1993). 'In The Mode'. Details. pp. 90–95, 168.

- ^'Collect-a-Page (Dave Gahan's questionnaire)'. Archived from the original on 27 November 2008.. Look In. Sacred DM. 5 December 1981.

- ^'Collect-a-Page (Martin Gore's questionnaire)'. Archived from the original on 27 November 2008.. Look In. Sacred DM. 12 December 1981.

- ^Painter, Ryan (28 May 2016). ''The Damned: Don't You Wish We Were Dead''. KUTV. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^'Excelsior Publications suspend Dépêche mode'. Stratégies (in French). 8 November 2001. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^Bell, Max (11 May 1985). 'Part 2 : Martin Gore – The Decadent Boy'. No1 Magazine. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007. Retrieved 29 October 2007.Cite uses deprecated parameter

deadurl=(help) - ^'Depeche Mode – the real origin of the band's name'. Eighty-eightynine. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ abDoran, John (20 April 2009). 'Depeche Mode Interviewed: Universal Truths And Sounds'. The Quietus. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ abcdefGiles, Jeff (26 July 1990). 'This band wants your respect – Depeche Mode may sell millions of albums and play to capacity crowds in huge football stadiums but these techno-pop idols still aren't happy'. Rolling Stone. TipTopWebsite.com. pp. 84–87. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^Tickell, Paul (January 1982). 'A Year In The Life of Depeche Mode'. Archived from the original on 8 August 2011.. The Face. Sacred DM.

- ^Paige, Betty (31 January 1981). 'This Year's Mode(L)'. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011.. Sounds. Sacred DM.

- ^ abc'Depeche Mode'. Official Charts Company. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^Colbert, Paul (31 October 1981). 'Talking Hook Lines'. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011.. Melody Maker. Sacred DM.

- ^Fricke, David (13 May 1982). 'Speak & Spell – Depeche Mode'. Rolling Stone. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- ^Ellen, Mark (February 1982). 'A Clean Break'. Archived from the original on 4 February 2014.. Smash Hits.

- ^Miller 2004, p. 103.

- ^Miller 2004, p. 107.

- ^Reinke, Stefan; Goh, Kerstin (16 November 2011). 'Erasure im Soundcheck'. Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^Miller 2004, p. 125.

- ^Miller 2004, p. 121.

- ^Miller 2004, p. 113.

- ^Miller 2004, p. 134.

- ^Malins 2001, p. 58.

- ^'The Singles 81–85'. Recoil.co.uk. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^Benne (3 May 2005). 'Inga Humpe – Mit Depeche Mode in einer 2raumwohnung'. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009. (in German). MUNA.

- ^Malins 2001, p. 82.

- ^Voss, B. (6 May 2009). 'Masters of 'The Universe''. David Atlanta. Archived from the original on 9 June 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^McIlheney, Barry (29 September 1984). 'Greatness and Perfection'. Archived from the original on 4 January 2009.. Melody Maker. Sacred DM.

- ^ abMalins 2001, p. 95.

- ^'Alan Wilder's history – Historical evidence Part 1'. Shunt. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^Adinolfi, Francesco (22 August 1987). 'Dep Jam'. Archived from the original on 26 August 2011.. Record Mirror. Sacred DM.

- ^'Music for the Masses – Depeche Mode'. Shunt. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^'Music for the Masses – Depeche Mode'. Shunt. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^Levy, Eleanor (3 October 1987). 'DEPECHE MODE 'Music For The Masses' (Mute STUMM 47)'. Archived from the original on 26 August 2011.. Record Mirror. Sacred DM.

- ^Erb, Nadja; Geyer, Steven (27 October 2009). 'Wir wären besser nicht aufgetreten'. Frankfurter Rundschau (in German). Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- ^Horáček, Michal (11 March 1988). 'Černá revoluce : Praha 1988 (díl 4.)'. Depeche.cz. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^Miller 2004, p. 265: Jonathan Kessler quoted in the 101 film. '$1,360,192.50. Paid attendance was 60,453 people, tonight at the Rose Bowl, Pasadena, 18 June 1988. We're getting a load of money. A lot of money; a load of money – tons of money!'

- ^Villar, Víctor R. (1 April 2009). 'Especial Depeche Mode: 101'. Hipersónica (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 6 November 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2010.Cite uses deprecated parameter

deadurl=(help) - ^'The Beginning of Depeche Mode's History'. Pimpfdm.com. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ^'Depeche Mode: 101 (1989)'. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^'MTV Video Music Awards – Performers'. MTV. Viacom. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^Miller 2004, p. 291.

- ^Tobler 1992, p. 472.

- ^'The BRITs 1991'. Brits.co.uk. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^Sanner, Stacey (21 March 1993). 'Depeche has faith in new 'Songs''. Variety. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^'Gold & Platinum – Depeche Mode – Violator'. Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ abMiller 2004, p. 299.

- ^Miller 2004, pp. 299–300.

- ^'Dave Gahan's Rock Awakening'. Contactmusic.com. 20 June 2003. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^'Songs of Faith and Devotion – Depeche Mode'. Recoil.co.uk. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^'37th Grammy Awards – 1995'. Rock On The Net. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- ^Ali, Omar (4 April 2001). 'In the Mode for Love'. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011.. Time Out. Sacred DM.

- ^Brown, Glyn (2 May 1997). 'Music a la Mode'. The Independent. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^'The Singles 86–98'. Recoil.co.uk. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^'Compact Space'. Compact Space. 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^'Sad Announcement: Alan Wilder left DM'. Archived from the original on 4 February 2014.. 2 June 1995.

- ^Miller 2004, p. 413.

- ^Brown, Mark (1 May 1997). 'Depeche vs. Drugs'. Winnipeg Free Press. Archived from the original on 26 January 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2014.Cite uses deprecated parameter

deadurl=(help) - ^Cameron, Keith (18 January 1997). 'Dead Man Talking'. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011.. NME. Sacred DM.

- ^Sexton, Paul (15 March 1997). 'Depeche Mode Back from the Brink'. Billboard. Vol. 109 no. 11. pp. 20–22. ISSN0006-2510.

- ^Miller 2004, p. 429.

- ^'Press Conference, Hyatt Hotel, Cologne Germany'. Archived from the original on 28 December 2012.. DepecheMode.com. 20 April 1998.

- ^'Exciter – Depeche Mode'. Metacritic. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- ^'Press Conference, Valentino Hotel, Hamburg Germany'. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012.. 13 March 2001.

- ^'Depeche Mode to Release 'One Night In Paris' as a DVD May 27; Will Include Bonus Footage and Special Features'. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.. Onipdvd.depechemode.com.

- ^'The Q Awards'. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013.. DepecheMode.com. 22 October 2002.

- ^'Martin L. Gore – Counterfeit²'. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014.Cite uses deprecated parameter

deadurl=(help). Martingore.com. - ^''DEPECHE MODE: TOURING THE ANGEL, LIVE IN MILAN', to Premiere Nationwide in a One-Night Big Screen Concerts(SM) Event'. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012.. Business Wire. 11 September 2006.

- ^'Depeche Mode – Touring The Angel: Live in Milan'. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.. Liveinmilan.depechemode.com.

- ^'2006 MTV Europe Music Awards – Best Group'. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013.. DepecheMode.com. 2 November 2006.

- ^'The Complete Depeche Mode'. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.. Thecomplete.depechemode.com. 19 December 2006.

- ^Van Isacker, B. (27 July 2007). 'New Depeche Mode album in the pipeline for 2008'. Archived from the original on 22 June 2010.. Side-Line.

- ^'Depeche Mode sign worldwide exclusive deal with EMI Music – to include the US for the first time'. Archived from the original on 23 June 2013.. EMI Music. 7 October 2008.

- ^Kirn, Peter (May 2009). 'Depeche Mode: Exploring Deeper Space on Sounds of the Universe'. Archived from the original on 5 May 2009.. Keyboard.

- ^'Depeche Mode Announces The Release of Sounds of the Universe 21 April 2009'. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009.. DepecheMode.com. 15 January 2009.

- ^'Depeche Mode on new CD out today and tour'. Archived from the original on 16 July 2012.. USA Weekend. 21 April 2009.

- ^'depeche mode dot com'. DepecheMode.com. Archived from the original on 7 September 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2010.Cite uses deprecated parameter

deadurl=(help) - ^Halperin, Shirley (24 April 2009). 'Depeche Mode Shut Down Hollywood Blvd for 'Kimmel''. Rolling Stone. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- ^Rogers, Georgie (7 October 2008). 'Depeche Mode tour'. BBC Radio 6 Music. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^Paine, Andre (28 May 2009). 'Depeche Mode Cancels More Dates As Singer Recovers From Surgery'. Billboard. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^'Depeche Mode joined by former band member at Teenage Cancer Trust show'. NME. 18 February 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ ab'Alan Wilder Rejoins Depeche Mode For One Song In London'. ChartAttack. 18 February 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^''Tour of the Universe – Live In Barcelona' – New Live Video'. DepecheMode.com. 23 September 2010. Archived from the original on 7 September 2009. Retrieved 26 September 2010.Cite uses deprecated parameter

deadurl=(help) - ^'Top 25 Tours of 2009'. Billboard. 11 December 2009. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

20. Depeche Mode

Total Gross: $45,658,648

Number of Shows: 31

Total Attendance: 690,936

Number of Sell-Outs: 9 - ^'Tour Of The Universe: Barcelona 20/21.11.09 CD+DVD'. Amazon.com. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- ^'Robbie Williams und Depeche Mode gewinnen ECHO 2010, Doppelerfolge für Jan Delay und Silbermond'. Echopop.de (in German). 5 March 2010. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014.

- ^Spitz, Marc (7 June 2011). 'Q&A: Martin Gore of Depeche Mode'. Vanity Fair. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ abYoung, Alex (18 November 2010). 'Depeche Mode members to reunite for new remix album'. Consequence of Sound. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ^'Vince Clarke, Alan Wilder remixing Depeche Mode tracks for CD expected next year'. Slicing Up Eyeballs. 16 November 2010. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ^Van Isacker, B. (28 November 2010). 'Duran Duran remix 'Personal Jesus' for upcoming Depeche Mode remix album'. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013.. Side-Line.

- ^'Depeche Mode 'Remixes 2: 81–11' Coming 6 June'. DepecheMode.com. Archived from the original on 7 September 2009.Cite uses deprecated parameter

deadurl=(help) - ^'Depeche Mode, Jack White, Patti Smith, Glasvegas help cover U2's 'Achtung Baby''. Slicing Up Eyeballs. 4 September 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^Bliss, Karen (9 September 2011). 'Bono Announces 'Achtung Baby' Covers Album'. Rolling Stone. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^'Depeche Mode plans 2013 album and tour'. CBC News. 24 October 2012.

- ^Young, Alex (11 December 2012). 'Depeche Mode to release new album in March'. Consequence of Sound. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^Battan, Carrie (24 January 2013). 'Depeche Mode Detail New Album Delta Machine'. Pitchfork. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ^'Depeche Mode announces North American dates for 'Delta Machine' summer tour'. Slicing Up Eyeballs. 11 March 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ^'Depeche Mode Hallentour 2013 / 2014 – Tickets Vorverkauf'. Vorverkaufstarts.de (in German). Archived from the original on 6 March 2016.

- ^'Die Gewinner 2014'. Echopop.de (in German). Archived from the original on 16 February 2015.

- ^'Echo 2014: Helene Fischer räumt ab' (in German). Laut.de. 27 March 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^'Depeche Mode Live In Berlin – Coming November 17th on Columbia Records'. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014.. DepecheMode.com. 8 October 2014.

- ^Grow, Kory (19 March 2015). 'Black Celebration: Depeche Mode Look Back on 'Violator' 25 Years Later'. Rolling Stone. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^'Episode 68 – Martin Gore from Depeche Mode'. The RobCast. 25 January 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^'Depeche Mode'. Facebook. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ^Grow, Kory (13 September 2016). 'Depeche Mode Detail Massive Video Box Set'. Rolling Stone. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^Pearce, Sheldon. 'Depeche Mode Announce New Album Spirit, Upcoming Tour'. Pitchfork. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ^Britton, Luke Morgan (18 October 2016). 'Rock And Roll Hall of Fame announce 2017 nominees: Depeche Mode, Kraftwerk, Tupac and more'. NME. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^O'Connor, Roisin (3 February 2017). 'Where's the Revolution? Depeche Mode release blistering new track'. The Independent. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^'The Global Spirit Tour'. Depechemode.com. 12 October 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^'Global Spirit Tour'. Depechemode.com. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^Sutton, Michael. 'David Gahan – Artist Biography'. AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^'Depeche Mode frontman Dave Gahan gets spiritual'. CNN. 8 June 2012. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^Unterberger, Andrew (28 April 2015). 'Martin Gore on His New Solo Album and No Longer Making Music for the Masses'. Spin. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

I remember buying [Brian Eno's] Music for Airports when it came out, and I think I was so young that it was the Roxy Music connection that made me go and buy it. But I used to listen to that over and over and over again. I know every single note on it.

- ^Whyte, Mike (28 April 2003). 'Martin L Gore on his own track'. Release Magazine. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^'Depeche Mode talk blues influence and unveil 'Heaven' video – watch'. NME. 1 February 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ abcAnkeny, Jason. 'Depeche Mode – Artist Biography'. AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ^ abSerpick, Evan (2001). 'Depeche Mode'. The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll. Simon & Schuster. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ^Cairns, Dan (1 February 2009) 'Synth pop: Encyclopedia of Modern Music'. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011.. The Times.

- ^ abcdeUnterberger, Andrew (21 March 2007). 'Depeche Mode vs. The Cure'. Stylus Magazine. Archived from the original on 11 March 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ^Breihan, Tom (14 February 2013). 'Watch Depeche Mode Play 'Heaven' Live'. Stereogum. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^Herrick, Keely (9 June 2014). 'Dave Gahan: Depeche Mode's frontman keeps on kicking'. AXS. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^Malitz, David (21 April 2009). 'Quick Spins: Reviews of CDs by Depeche Mode, Allen Toussaint and Wussy'. The Washington Post. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^'New Music Report: Asher Roth and Depeche Mode's Albums'. Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 26 April 2009.

- ^Bliss, Karen (19 July 2009). 'Electro-rockers Depeche Mode touring the Universe'. Toronto Star. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^Sutcliffe, Phil (June 2009). 'Depeche Mode'. Mojo. Rock's Backpages. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^Greenblatt, Leah (15 April 2009). 'Sounds of the Universe (2009)'. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^Wood, Mikael (17 April 2009). 'Depeche Mode, 'Sounds of the Universe' (Mute/Capitol/Virgin)'. Spin. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^Sason, David (4 August 2009). 'Interview: Depeche Mode's Andrew Fletcher'. North Bay Bohemian. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^Allan, Richard (2003). Buckley, Peter (ed.). The Rough Guide to Rock (3rd ed.). Rough Guides. ISBN1-85828-457-0.

1992 saw the release of an EP, Broken, produced by Flood, better known for his work with British pop-rock band Depeche Mode.

- ^Gourlay, Dom (4 April 2013). 'Depeche Mode – Delta Machine Album Review'. Contactmusic.com. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

Over the course of their previous twelve albums, they've embraced any number of genres from avant-garde electronica, pop, soul, techno, industrial rock and even metal.

- ^Baker, Trevor (2013). Depeche Mode – The Early Years 1981-1993. John Blake Publishing Ltd. p. 74.

- ^'Depeche Mode'. Rock's Backpages. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^Vineyard, Jennifer (24 April 2013). 'Catching up with Depeche Mode'. CNN. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^'Martin Gore (Depeche Mode) interview'. YouTube. 22 February 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^Condran, Ed (25 May 2006). 'On That Note: Comeback Mode'. Archived from the original on 22 July 2015.. South Philly Review.

- ^'New Depeche Mode album number one in 20 countries'. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011.. EMI Music. 1 May 2009.

- ^Frere-Jones, Sasha (5 June 2006). 'Atlantic Crossing'. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014.. The New Yorker.

- ^Smith, Sean (2013). Gary: The Definitive Biography of Gary Barlow. Simon & Schuster. p. 18. ISBN978-1-47110-224-0.

- ^'The Things You Said ..' Archived from the original on 4 April 2007.. DepecheMode.co.il. 12 March 2005.

- ^Dufrene, Zach. 'Electronic Music Realm: The 100 Greatest Artists of Electronic Music (1–20)'. Electronic Music Realm. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^'The Top 1000 Artists of All Time'. Acclaimed Music. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^Eglinton, Mark (10 June 2009). 'He Travels: Jim Kerr of Simple Minds Interviewed'. The Quietus. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^Frith, Holly (12 April 2011). 'GWEN STEFANI: NO DOUBT RECORDING DEPECHE MODE INSPIRED ALBUM'. Gigwise. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ^ abcdeTrendell, Andrew (11 February 2014). 'From Crosses to Muse and The Killers: 10 bands inspired by Depeche Mode'. Gigwise. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^Scrudato, Ken. 'Dave Gahan and Brandon Flowers'. Working Class Magazine. No. 7. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2011.Cite uses deprecated parameter

deadurl=(help) - ^Apar, Corey. 'Chester Bennington – Artist Biography'. AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved 9 September 2007.

- ^'Depeche Mode 'Remixes 81-04''. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007.. Mute.

- ^'The Crystal Method'. Answers.com. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ^'An exclusive interview with Fear Factory's Raymond Herrera'. Archived from the original on 5 January 2012.. Prog4you.com.

- ^Wøien, Kim (4 September 2009). 'Et intervju med La Roux' (in Norwegian). Musikknyheter.no. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^Giles, Jeff (20 June 2012). 'Gotye's Biggest Influences: Depeche Mode, Ween + More'. Diffuser. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ abGrow, Kory (11 August 2015). 'Are Depeche Mode Metal's Biggest Secret Influence?'. Rolling Stone. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ^Kruspe, Richard (20 May 2011). 'Rammstein Pounding the European Metal Hammer'. Archived from the original on 26 June 2011.. Jam Magazine Online.

- ^Van Isacker, B. (28 July 2009). 'A-ha cover Depeche Mode's 'A question of lust''. Archived from the original on 14 September 2011.. Side-Line.

- ^'Win & Régine from Arcade Fire interviewed (July 2010)'. YouTube. 13 July 2010. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^Savage, Mark (31 December 2012). 'BBC Sound of 2013: Chvrches'. BBC News Online. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- ^'3. Music. – Information'. 10 Years of Being Boring. 9 September 2007. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^'Absolutely Pet Shop Boys'. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012..

- ^Buckley, David (March 2012). 'Last night a record saved my life: Gary Numan'. Mojo. No. 220. p. 29.

- ^Freedom du Lac, J. (11 September 2005). 'Depeche Mode'. The Washington Post. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^'Depeche Mode: Charity Work, Events and Causes'. Look to the Stars. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^Diderich, Joelle (30 January 2014). 'Hublot and Depeche Mode Link Up to Benefit Charity: Water'. WWD. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^'Depeche Mode and Hublot Raise 1.4 Million Dollars for Charity: Water'. Geneva Seal. 5 August 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

Bibliography[edit]

- Malins, Steve (2001). Depeche Mode: A Biography. André Deutsch. ISBN978-0-233-99430-7.

- Miller, Jonathan (2004). Stripped: The True Story of Depeche Mode. Omnibus Press. ISBN1-84449-415-2.

- Tobler, John (1992). NME Rock 'n' Roll Years (1st ed.). London: Reed International Books Ltd. ISBN0-600-57602-7.

Further reading[edit]

- Corbijn, Anton (1990). Depeche Mode: Strangers. Prentice Hall. ISBN0-7119-2493-7.

- Thompson, Dave (1995). Depeche Mode: Some Great Reward. Pan Macmillan. ISBN0-283-06243-6.

- Zill, Didi (2004). Depeche Mode. Photographs 1982–87. Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf. ISBN3-89602-491-4.

External links[edit]

- Depeche Mode at Curlie

- Depeche Mode International at Smule